Adrian Belmes

Pop literary culture has seen a particular resurgence in stories reworking mythology. Particularly when it comes to Greek myth, they tend to be one of a few categories: lush fantastical romancitizations, or action-packed warrior adventures, or modern applications of the same old classics. Consider The Song of Achilles, or the entire Percy Jackson series, for recent examples.

Pop literary culture has seen a particular resurgence in stories reworking mythology. Particularly when it comes to Greek myth, they tend to be one of a few categories: lush fantastical romancitizations, or action-packed warrior adventures, or modern applications of the same old classics. Consider The Song of Achilles, or the entire Percy Jackson series, for recent examples.

Dreamlives of Debris, however, is none of those things.

Published just earlier this year, Dreamlives of Debris is the latest of author Lance Olsen’s 13 novels. Olsen has received multiple awards for his work, including the Berlin Prize and a Pushcart. His novel Tonguing the Zeitgeist was a finalist for the Philip K. Dick Award. Olsen has been called the father of innovative literature and was formerly the governor-appointed Writer-in-Residence of Idaho. Currently, he teaches experimental narrative theory and practice at the University of Utah, though he has taught all around the world. I recently had the honor of interviewing him. The intellect and creativity of the man is awespiring, and that really shines through in Dreamlives.

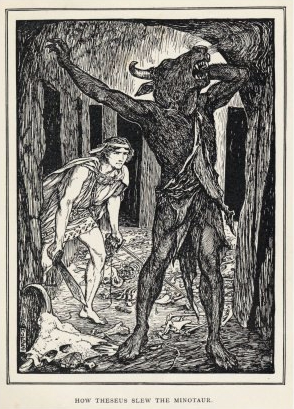

It’s difficult to pin down in any brevity what Dreamlives is about. At the most basic level of explanation, it is a retelling of the Minotaur myth as narrated by Debris, a representation of the minotaur herself. Olsen seems to purposefully obscure the exact nature of Debris. She is described equally as literally monstrous and in human terms. In the foreword by Lidia Yuknavitch, she is “a beautiful, disfigured little girl”. Debris behaves, though seemingly not of her own volition, as something of a conduit for all the debris of history, which manifests as a multitude of voices interrupting her thoughts.

These voices she calls “screamings” speak both to her and through her in an orchestrated cacophony of stimuli and information, a representation of our own modern state of data overload. The references are infinitely vast and perform in a web of interconnectivity, playing masterfully off one another and the core fiction of the narrative. They vary from to Sir Arthur Evans and Saint Thomas Aquinas, to Michel Foucault and Denis Diderot, to Stuxnet and Julian Assange. I attempted to track my discoveries and build a map of Olsen’s masterfully cartographed architecture, but I could spend years studying only this book and still not grasp on all the references in it. I did manage to scrounge a few up from their sources. “Journey-From-Ass-To-Soul Song,” for example, quotes an article about a Berlin nightclub. “Professor Anne P. Chapin Song,” I suspect is taken from her piece on Minoan frescoes in The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age: Aegean. I do not encourage any reader of this book to take upon themselves the task of dissection unless they are as obsessive as I or Olsen. Perhaps this is what he getting in Deamlives’ commentary on the overwhelming state of information in the present.

Olsen crafts something of an insane spiral of recursion. Every connection feels like a discovery. One that particularly stood out to me was the “I Love You Song”, a reference to the ILOVEYOU computer virus that spread in the early 2000s. The first mention describes the spread of the literal virus as a consequence of human sentimentality, “because millions of people one day innocently opened our email attachment labeled I love you”. A subsequent entry conflates the computer virus to the advent of the AIDS virus into a global pandemic, painting the image of its inception as “one evening a muscular black teen in Kinshasa innocently [slipping] a forkful of infected chimpanzee meat between his lips”. It’s powerful stuff.

On a far less philosophical note, seeing Slavoj Zizek get some airtime gave me a laugh. I’m fairly certain the included fragment of commentary on Kubrick’s The Shining was pulled directly from The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, one of my favorite films that I would say is about as bizarrely metaphysical as Dreamlives is. However, I cannot say if my assessment is correct, as Olsen has himself admitted that some of the quotations are pure invention. I discovered this myself while researching the book. With the intentional blending of truths and half-truths across the web of history, Dreamlives traipses along the concept of historiographic metafiction. If you’d like to read a little more about that, check out my article about the history of the genre.

There are really two sides to this narrative. There is Debris and her voices, but then there  is also the web of mythic heroes–dare I call them heroes– of the Minotaur myth and its related web of stories. Theseus, Deadalus, Pasiphae, Apis the Healer, Lady Tiresias, Araidne, and many others are all given life and character full of human complexities through Debris’ relations and their own interruptions of her narration. Debris says at one point that, “what I am telling you, I want to say, is a love story”. In a way, it is. Dreamlives beautifully explores the ugly complications of love. It does not shy from the painful realities typically overlooked by myths in their original tellings. Jealous Deadalus “claps Perdix between the shoulder blades affectionately, then not,” killing him for fear of his fame. Pasiphae participates in the implied rape of Debris by Apis the Healer, Debris saying that this is “about how deeply family members can care for one another”. Ariadne is either sexually used by Theseus, or comes upon “Dionysus on his knees, fingers grabbing under Theseus”, resulting in her death. These otherwise mythic characters are transmuted into reality out of concept by the unflinching exhibition of their human darkness.

is also the web of mythic heroes–dare I call them heroes– of the Minotaur myth and its related web of stories. Theseus, Deadalus, Pasiphae, Apis the Healer, Lady Tiresias, Araidne, and many others are all given life and character full of human complexities through Debris’ relations and their own interruptions of her narration. Debris says at one point that, “what I am telling you, I want to say, is a love story”. In a way, it is. Dreamlives beautifully explores the ugly complications of love. It does not shy from the painful realities typically overlooked by myths in their original tellings. Jealous Deadalus “claps Perdix between the shoulder blades affectionately, then not,” killing him for fear of his fame. Pasiphae participates in the implied rape of Debris by Apis the Healer, Debris saying that this is “about how deeply family members can care for one another”. Ariadne is either sexually used by Theseus, or comes upon “Dionysus on his knees, fingers grabbing under Theseus”, resulting in her death. These otherwise mythic characters are transmuted into reality out of concept by the unflinching exhibition of their human darkness.

Perhaps the most curious quality of the book as a whole is its structure. Dreamlives in itself is a labyrinth, featuring no page numbers by which one can orient themselves by. Pages are arranged with perhaps only a single “:::: Voice” speaking, or multiple all at once. No two pages look truly alike, though the visual coherency flows beautifully. Occasionally within the landscape, a purposeful moment of formatting insanity will present itself. “Catastrophe Chorus”, for a dramatic example, features disjointed phrases scattered physically across the page, as though all the text save for a few select words was whited out. The liquid architecture of the text speaks to the physicality of the labyrinth, as “sometimes the walls become a whirlwind of hands or dying alphabets”. It is a lyrical, philosophical experiment in construction that echoes the fluidity of the language and the narrative itself.

Dreamlives of Debris is something of an exercise in literature, intent to engage all parts of your thinking. It is impossible to read this book with any lethargy. Exploration is encouraged by fault of form, opening up limitless possibilities of interpretations spiraling around the concepts of truth, data, and interconnectivity. I encourage readers seeking to engage deeply with the metaphysics of their reading to get lost in this labyrinth.

Currently, Olsen is working on a new book, an interconnected web of short stories about Berlin and its people in the unusual, ephemeral period between the close of WWI and the fall of the Weimar Republic. You can keep up with him on his website.